As a scholar, my job consists of assimilating and disseminating information. The process of reviewing books entails both. My method prioritizes efficiency: reading as quickly as possible with as much comprehension and long-term retention as possible. The information also needs to be stored in a format that makes scholarly work on the material easy. For me, reading is aimed at reviewing; reviewing completes the process of reading. A book is assimilated only when I can express my reflections on it. The method is divided into three steps: 1) setting up the reading environment; 2) reading and taking notes; and 3) drafting the review.

1. Setting Up the Reading Environment

Reading is both a physical and mental activity. People vary as to what they find congenial writing environments, but some physical requirements are invariable. My method uses 1) a book stand, 2) a physical book, 3) a pencil, and 4) a computer. The book’s spine should be broken in to the point that it will lie flat on the book stand without falling shut. If you have to keep holding the book open, you can’t type with both hands. (If you can’t type with both hands, learn.)

The book stand should be positioned so that the book hits your eyes at a 45-degree angle. This improves reading speed. To minimize eyestrain, lighting should be bright but diffuse. Diffuse lighting is generally from multiple sources or sunlight and doesn’t cast dark, sharp shadows when you hold your hand over the page. You should be able to see both the book and the computer without turning your neck too far. For typing ease, your computer’s resting surface should be at about elbow height when you’re sitting with your arms hanging down. Too high and you will scrunch your shoulders. All of these factors are aimed at allowing you to read comfortably for long periods of time. The book stand is especially important, since you lose too much time typing if you keep setting the book down and picking it up again or try to hold it one hand.

2. Reading and Taking Notes

a. Setting Up the Note File

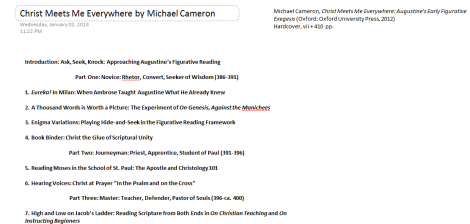

A few minutes of preparation before reading saves time later. I create a file in OneNote, but other programs are fine. I type the title and author in the page title slot. Then, I type next to it the complete bibliographic information. I operate under the assumption that I may never see this physical book again; this note file needs to contain everything necessary for the review and any future scholarly work. Then I go to the table of contents and copy the chapter headings, giving me a skeleton for my notes. Here is an example of the first stage of setup:

b. Reading and Taking Notes

I take notes by chapter; if the chapters are unusually long, I may subdivide the chapters into sections. With a pencil in hand, I focus on reading quickly but thoroughly. When I see a section that looks significant, such that it might be worth making a note, I mark its boundaries in the page margin with my pencil. I don’t write comments or underline each word, because the goal is to interrupt reading as minimally as possible. When the chapter or section is finished, I go back and decide whether the sections I marked are really worth making into notes. Often I find that a passage I marked contains a concept that the author expresses more succinctly later in the section, or even that the idea wasn’t as profound as I originally thought. Sometimes I read books without my pencil, typing notes as I go, and I always end up taking too many notes.

Having chosen the passages, I make a few types of notes. Regardless of the type of note, I always include the page number(s)! A note without page number is worthless for citing later. The first type is a verbatim quote. I make these fairly often, but I tend to sprinkle ellipses liberally to condense the best parts of paragraphs. The second is a paraphrase, in which I state a proposition from the book in my own words. The third just marks content that didn’t get detailed notes. For example, recently I came across a section on Manichean beliefs in a book about Augustine. This section wasn’t particularly relevant to my current resource, so I didn’t take any detailed notes, but I wrote “Manichean beliefs – 72-84” so I would know this section was there in case I need to look up that topic later.

Sometimes I mark up my notes to make them more useful. I often preface a note with a topic to put it in context. For example: Ambrose’s influence, “quoted portion.” If there is a key word or phrase embedded in a longer quote, I highlight it. Likewise, I might mark listed items embedded in a paragraph. If a particular claim seems unsupported or I suspect the author has made a factual error, I mark the note in red.

c. Writing a Chapter Summary

Once the notes on the chapter are finished, I go back to the beginning of the chapter in my note file and write a summary of it. The summary is really more like a mini-review, as I am already thinking about and interacting with the material. The goal is to write the summary using only the notes in my file. If I did a good job understanding what I read and took good notes, I won’t have to refer back to the physical book. If I do, I may take an additional note or two to remedy the situation.

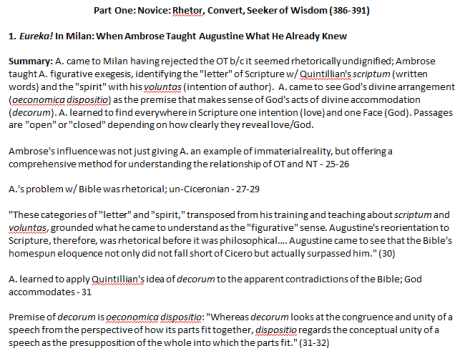

Here is an example of a section of notes:

3. Drafting the Review

A book review’s purpose is to allow the reader to determine whether to read the book and what priority to place on doing so. The reviewer does not just give a generic recommendation, because people are not generic. The reviewer needs to keep in mind individual readers’ interests and abilities. I am still developing my style as a reviewer, but I make adjustments based on the criterion of the review’s purpose. [My reviews are listed here.]

My first paragraph gives a general overview of the book. I introduce the author and outline the theme and general plan of the book. A few body paragraphs summarize the content of the book. However, a review is not an abstract. I try to take a few body paragraphs to highlight remarkable themes or arguments. Here I interact with the book, offering some evaluations and showing how it has influenced my thinking. Toward the end I try to make general remarks about register (academic, literary, popular) and style. I offer an evaluation of the book as a whole and suggest what types of readers would benefit most from it.

The review completes the process of reading by forcing me to think through how the book as a whole fits into my broader intellectual development. It is only in teaching, in the sense of speaking authoritatively to others after a period of reflection, that one completes learning.

—————

The above is my method. Was this helpful? Do you have questions? Do you want to share your own methods?